If you’re involved in any element of product/service design or development, innovation or growth (etc.) at your organization, chances are you’ve at least heard of Design Sprints. Because of their bias for action, repeatable systematic steps and their powerful risk mitigation qualities, design sprints have caught on like wildfire, especially in the US and Europe. Increasingly, they’re making their way into the Canadian business landscape.

Developed and refined by Jake Knapp, John Zeratsky and Braden Kowitz while at Google Ventures, Design Sprints offer a structured process for teams to focus their energy to solve big challenges in a very short time frame.

But what are Design Sprints, exactly? Why should companies (or teams) care? Should you bring them into your organization? What should you consider before, during and after the sprint? What kind of problems are Design Sprints most effective at solving?

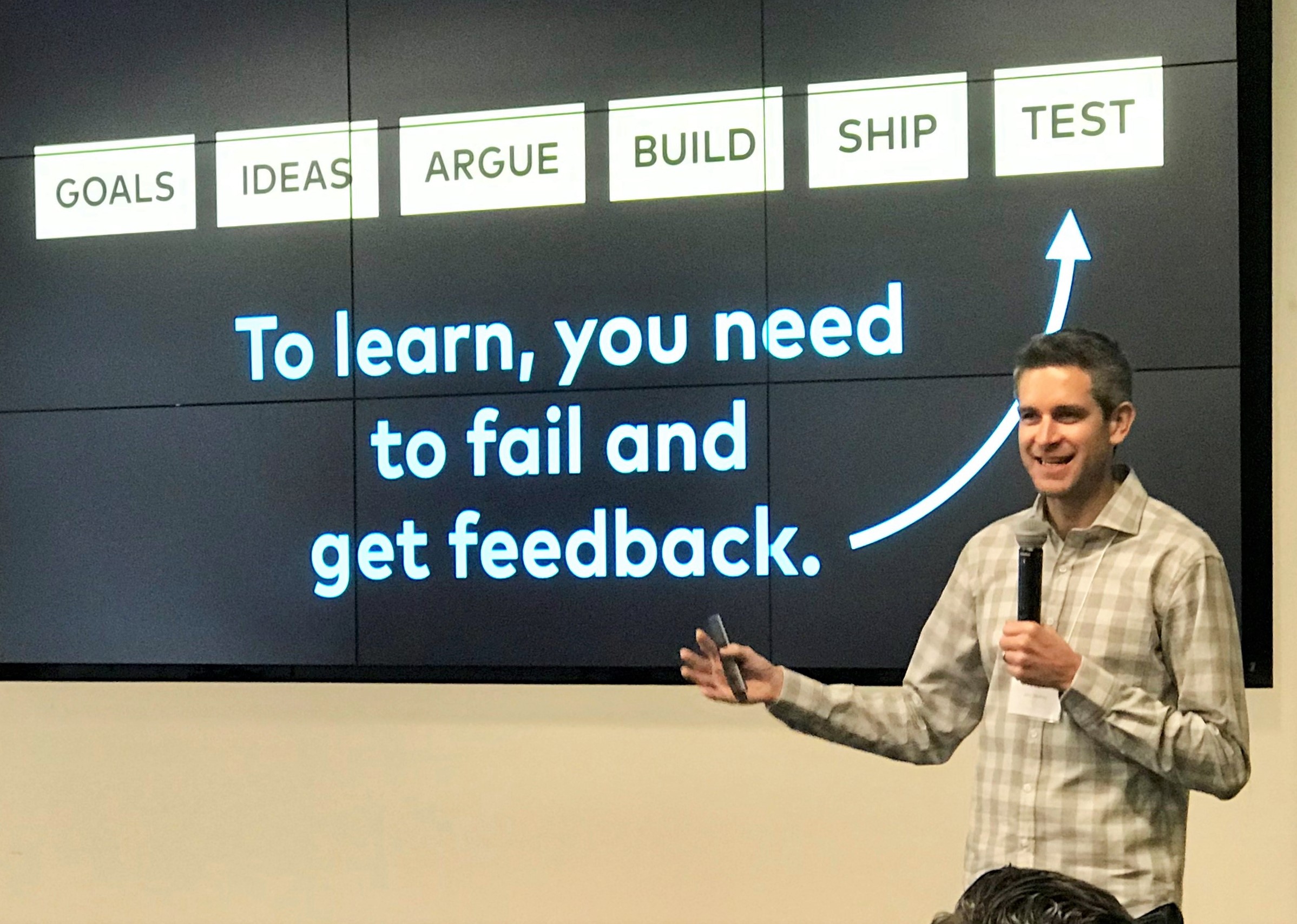

We sat down with John Zeratsky, process co-creator and co-author of the seminal book, Sprint: How to Solve Big Challenges and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days to dig into these questions (and more!). John offers a uniquely expert (inside) view of the Design Sprint as a powerful collaborative tool that helps teams focus and solve big organizational challenges – faster.

Last June we were delighted to partner with John to launch the Official Design Sprint Bootcamp for the first-time ever in Canada. It was an awesome day of learning and we’re thrilled John will return to Toronto with his Bootcamp on November 19.

Design Sprint Q&A with John Zeratsky

Q: How did you come to be involved in the Design Sprint process at GV with Jake Knapp and Braden Kowitz?

I joined Google Ventures (GV) in 2011 as the second design partner. During my first year, Braden and I would just sort of go from startup to startup, doing our best to help them as designers. But as GV did more and more investing, it became clear that we couldn’t rely on our expertise to help every company, and we couldn’t possibly scale to serve the entire portfolio!

We knew Jake, and we had had some exposure to his early experiments with the Design Sprint, so we recruited him to join our team in 2012 and we began developing the process together.

Q: In the Sprint book’s preface, Jake states that your key role in each Sprint was keeping the sprints aligned with business goals – can you explain why that was important, and how it helped shape the way in which the team both ran and refined the Design Sprint process?

At first, I was the only person on the team who had run a small business and worked at a startup. (Daniel Burka had a similar background to mine and he joined the team in 2013). So as we developed the Design Sprint process, I was always thinking about what entrepreneurs cared about, and how we could make our sprints super valuable to their businesses.

Among the team, I was probably the most hardcore about keeping the process lean and focused. All businesses, but startups in particular, are full of questions about what to do and how it’ll work out. So I tried to keep our team focused on building a process that would help entrepreneurs answer those critical questions as quickly as possible.

Q: Having now run hundreds of Design Sprints as well as sprint trainings/bootcamps, what jumps out at you the most about the process itself, and the way in which people (and organizations) absorb and adopt it into their toolbox?

Two things:

First, the ability to answer important questions in a rapid and structured way. A lot of entrepreneurs talk about validating assumptions, but it can be hard to find and implement good methods for doing that in a practical way.

Second, it really struck me how much value there was in simply giving teams an excuse to focus together on the work that matters. Everyone spends so much time doing email and sitting in meetings, and it can be really tough to carve out time to do the essential work. Design Sprints create a structure for making that time.

Q: Are there some not-so-obvious benefits you wish people would talk about or highlight more often?

In some ways, the Design Sprint is just an elaborate trick to get teams to run customer research. That’s the most valuable part of the week, but it sometimes gets overshadowed by the more exciting and visually appealing steps that involve sticky notes and sketching.

Q: You’ve mentioned Design Sprints are effective de-risking/risk mitigation tools – how so?

When you’re working on something new, so many of the risks have to do with customers: Will customers care? Do you have the right solution? Does the solution actually solve the customer’s problem? Will they be willing to pay? (And every business has “customers,” even if they’re enterprise buyers or internal stakeholders).

When you’re working on something new, so many of the risks have to do with customers: Will customers care? Do you have the right solution? Does the solution actually solve the customer’s problem? Will they be willing to pay? (And every business has “customers,” even if they’re enterprise buyers or internal stakeholders).

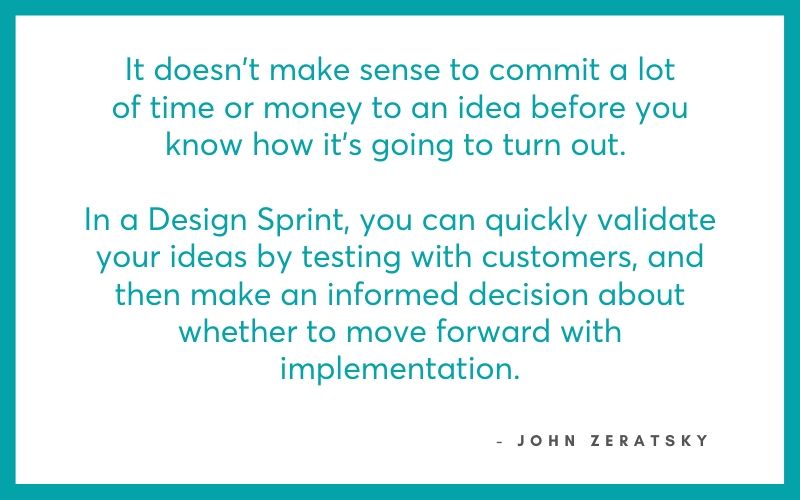

It doesn’t make sense to commit a lot of time or money to an idea before you know how it’s going to turn out. In a Design Sprint, you can quickly validate your ideas by testing with customers, and then make an informed decision about whether to move forward with implementation.

The Design Sprint is optimized for answering these kinds of questions.

You get a chance to test ideas and assumptions in a safe environment, by putting a prototype in front of five customers at the end of the week. It’s a far safer—and faster—way to validate your work than by launching into the market.

Q: You’ve also mentioned that the best Sprint projects are high-risk with uncertain outcomes — why is that?

Because these projects have the highest stakes.

Low effort projects can be tested with a quick implementation and experiment. And high-effort, low-uncertainty projects are good candidates for a simple ROI assessment and decision.

Q: Within that category of high risk/uncertain outcomes, are there particularly types of challenges/problems/scenarios for which Design Sprints are particularly well-suited?

The Design Sprint ends with a customer test, so the process is particularly well-suited to projects where the big questions have to do with customer reactions or preferences. If you’re wondering, “is it technically feasible to do this?” that is not a great question for a Design Sprint.

The Design Sprint ends with a customer test, so the process is particularly well-suited to projects where the big questions have to do with customer reactions or preferences. If you’re wondering, “is it technically feasible to do this?” that is not a great question for a Design Sprint.

But if your questions contain the words “human,” “customer,” “people,” etc, it’s probably perfect.

Q: How “big” or complicated should a problem be for a Design Sprint to be effective? Is there a such a thing as “too big”?

Not really. I have worked on Design Sprints where we launched novel new products, established new lines of business, tested services that would take two years to build, and even helped enroll more cancer patients in clinical trials.

Big problems are great for Design Sprints; the challenge is to find the specific question or moment you can target in your sprint and test with customers.

Q: This brings me to another question; how do teams ensure they’re focusing on the right problem? How much (and what kind) of time and effort should be devoted ahead of the Sprint to make sure?

In addition to the criteria above, there should be a sense of urgency and need around solving the problem. Don’t do a Design Sprint just to try it, or because it sounds interesting.

Here’s another rule of thumb: The idea of spending five days on the particular problem should feel like an opportunity, not a burden.

Q: Enterprise organizations are complex ecosystems. What’s the best way, in your opinion, to ensure firstly that the DS isn’t run in an isolated bubble; and that secondly, it can be integrated back into the organization when it’s done (that the outcomes of the DS have a life beyond the sprint week)?

It’s important that the real team is involved in running the sprint. It shouldn’t be done as a special project off in a special room with a special team. When a Design Sprint empowers an existing team to focus together on their most important challenges, it greatly increases the success rate of that sprint.

the success rate of that sprint.

In large organizations, you need to pay special attention to stakeholder involvement. You can’t have everyone in the room, but you can use “cameo appearances” to bring decision-makers in at critical moments.

And you can share the work that’s happening in a sprint via daily “show and tell”: invite stakeholders to come by for a quick review of the day’s work.

Q: What would you say to a leader or manager hesitant to try Design Sprints in their organization?

I would start by asking questions:

- Does your team have the time, tools, and processes needed to do what you’re asking them to do?

- Are you happy with the progress that’s being made on new projects and important initiatives?

- Are you being honest about the assumptions you bring into each project?

- If you support or approve a particular solution, how confident are you that it’s going to work?

Q: Having gone through a rigorous experimentation and refinement process to uncover the “ideal” Sprint, what are your thoughts on shortened or condensed Sprints – do you think they’re as effective?

Four-day sprints are equally effective and totally doable, especially by experienced teams. Three-day sprints can work as follow-up or iteration sprints.

The question(s) I have about shorter sprints would be: What are you giving up? Each step of a Design Sprint is there for a reason. Which one are you willing to do without?

Another important consideration is the sustainability of a faster pace. Burnout is a real issue for everyone, and super-condensed sprints tend to create a “hangover” effect as teams struggle to recover from an overly intense couple of days.

Q: You focus on and write a lot about making the most of time – I think I heard you call it “designing time” once. How would you convince a leader to invest five full days for a team to run a Design Sprint in our “busy” culture?

I wouldn’t make it about the sprint process.

I’d make it about the work—the challenge and importance of whatever project you’re considering for a Design Sprint. If you can’t justify spending five days on your most important project, what are you doing at work that’s more important?

In addition to the benefits of focus, and the Design Sprint’s structured processes for ideation and decision-making, the amazing result is that you actually get better and more efficient at doing the rest of your work, too. For example, there’s research showing that people who check email less often are less stressed (duh) but also measurably better and faster at managing email.

This phenomenon applies to all of our work—when we shift non-essential work from the foreground to the background, we become better at giving it just enough time and energy, instead of letting it take over our day.

Q: Shifting gears a little bit… What advice do you have for successful Design Sprint facilitation? How skilled and experienced should the facilitator be? Should they be an entirely neutral party? What should you do if you don’t have a strong facilitator in-house?

Good Design Sprint facilitation does require a degree of neutrality. But it’s also really valuable to have this capability in house. So I don’t recommend that teams pull in an outside facilitator for every single sprint. That said, it can be a good way to get started with the process, and an experienced outside facilitator can help to train your internal facilitators.

Good Design Sprint facilitation does require a degree of neutrality. But it’s also really valuable to have this capability in house. So I don’t recommend that teams pull in an outside facilitator for every single sprint. That said, it can be a good way to get started with the process, and an experienced outside facilitator can help to train your internal facilitators.

For internal facilitators, look at people in roles like customer research or customer success, where they are already used to asking (and answering) questions without too much bias.

If your organization has dedicated project managers, they can become great sprint facilitators too.

Another suggestion is to look at adjacent teams for people with the right skills but less attachment to the specific outcomes of the Design Sprint.

Q: What are the most common misconceptions you hear about Design Sprints? What do you think people tend to get wrong or misinterpret about them?

- “The Design Sprint is a recipe for innovation”

It’s not. It’s a process for helping teams focus together on their biggest challenges. The time and space created by a sprint can often lead to innovative solutions as a side effect, but it’s not the primary benefit. - “The Design Sprint only works for new products”

The process excels at improving existing products, adding features, or reaching new customers with the same product. In fact, those sprints go faster because the map (of how customers interact with the product) is already well understood. - “The Design Sprint only works for consumer products”

Close to half of the Design Sprints I’ve done were about enterprise products. The process works really well. The biggest challenge is finding customers for Friday’s test, but we can almost always turn tothe team’s network to recruit those people. - “The Design Sprint won’t work for my project”

As long as you’ve got a big challenge that’s tough to execute with uncertain results, and as long as it involves customers (internal or external), you can use a Design Sprint to answer your big questions about that project.

Q: What are the three most important learnings attendees can expect to get out of the Official Design Sprint Bootcamp in Toronto on November 19, 2019?

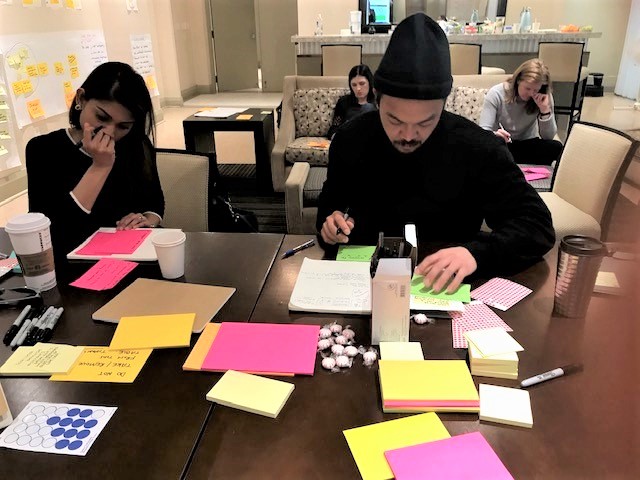

- An in-depth introduction to the Design Sprint, a five-day process that helps teams focus together on their biggest challenges.

- Real-world examples and case studies that’ll help attendees understand how the process can be used and how it applies to their work.

- Hands-on experience running a Design Sprint, so teams can go back and run their own sprints with confidence.

Q: Why should companies/organizations consider sending small teams to the bootcamp?

The Design Sprint process is for teams. And it requires a great deal of trust to work best. The bootcamp is an excellent way to give teams a group introduction to the process and help them build the trust and confidence to run sprints together on their own.

About John Zeratsky

John was a former design partner at Google Ventures, where he worked with Jake Knapp to develop the Design Sprint process. Since 2011, he has run well over 150 sprints. In 2016, John, Jake and Braden Kowitz published the New York Times bestselling Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days.

John was a former design partner at Google Ventures, where he worked with Jake Knapp to develop the Design Sprint process. Since 2011, he has run well over 150 sprints. In 2016, John, Jake and Braden Kowitz published the New York Times bestselling Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days.

John and Jake also published their second book, Make Time: How to Focus on What Matters Every Day in 2018.

Since publishing Sprint, John and Jake have been travelling the world running the Official Design Sprint Bootcamp. We’re super absolutely thrilled to be working with John again on the second-ever Official Design Sprint Bootcamp in Canada on November 19! This is an event you don’t want to miss.

Design Sprint & Innovation Masterclass

John’s bootcamp is Day 1 of a premium three-day Design Sprint & Innovation Masterclass that includes a deep dive into prototyping and testing with former Google Xers, Prototype Thinking Labs, and a third day focused on advanced facilitation.

Need help or support bringing Design Sprints into your organization? We can help! Visit our design sprints page for more info or email us any time.